How grief looks and feels

Grief is a natural emotional reaction to any type of loss. You most commonly feel grief after a death, but you may grieve other kinds of losses as well.

When a child is diagnosed with a serious illness, every member of the family and community may feel some sort of grief for the loss of good health, loss of normal routines, and loss of hopes and plans for the future.

Parents, the child, and other family members each have their own reactions and ways of dealing with their feelings. Grandparents experience grief directly for their grandchild, but they also grieve for the losses that their own child feels as the parent of a seriously ill child. Siblings grieve differently depending on their ages and abilities. Very young children who do not understand what is going on grieve for the loss of attention from their parents. Older children who understand what is happening grieve for their ill sibling, for changes in family routines, and for the loss of their parents’ attention.

When a child is diagnosed with a serious illness, parents, the child and other family members feel grief about many different kinds of losses. The grief includes:

- Grief for what has happened

- Grief for what could happen

- Grief for what will happen

Grief for what has happened

When a child is diagnosed with a serious illness, parents, the child, and other family members each have their own reactions and ways of dealing with their feelings. You may feel shocked or numb. You may feel overwhelmed with sadness, anger, disbelief, fear, worry, guilt, or helplessness. You may feel like you can’t do anything or you might try to do everything you can think of right away.

Over time, you, your child and your family may get more used to the news about the diagnosis. The healthcare team, the hospital, routines and medical procedures will feel more familiar. That does not mean your worries or feelings of grief will go away completely, but you may find new ways to live with this new experience. During this time, you and your family may feel grief about things that have already happened such as:

- Changes to your child’s body or abilities

- Separations while your child was in the hospital

- Loss of “normal” routines of day-to-day life

- Changes to finances and work

- Changes to future plans and hopes

This kind of grief can feel like sadness, longing, or wishing for something that was lost.

Grief for what could happen

You, your child and family may also worry about things that could happen, like:

- Pain or discomfort from procedures or treatments

- Possible side-effects of treatments or medication

- Changes to the child’s condition and abilities

- How the family will be able to take care of the child’s needs

- Effects of the child’s illness, treatment and care on other family members

- What might happen if or when the child dies

This kind of grief may feel as though you are “on the edge,” afraid to let your guard down, in case something bad happens while you try to protect your child and family.

Grief for what will happen

“Anticipatory grief” is a term that describes the way people feel when they expect that someone is going to die. In many ways, this grief feels like the grief after getting a diagnosis, or after a person dies. When you realize that your child’s death is coming closer, your thoughts and feelings of grief get stronger, and it may be even harder to focus on anything else.

In some situations, you may feel relief or “anticipatory relief” at the idea that your child’s suffering, or the strains on your family may soon end. This does not mean that you wish or want your child to die, just that there may be some small relief from all the heartache and grief.

Tyler gave us every minute he could and not a minute longer and I am grateful for that but I would not wish him back the way he was at the end. There is some sort of peace in all of that.” – Darren, father of Tyler

Waves of grief

Many people talk about the “stages of grief,” however grief does not happen in neat or predictable stages. There is no “right” or “normal” way to feel, no predictable order, and one feeling (or “stage”) does not always end before another one begins. Grief is messy. Another way to think about grief is that it comes in waves that shift and change over time.

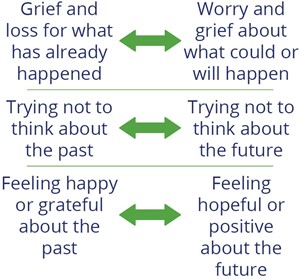

Over time, grief goes back and forth between:

These waves of grief are different for each person. You may “cope well” for a while and then feel a new wave of grief or worry. New waves of grief can be caused by things like:

- New or changing symptoms

- Medical procedures, tests or results

- Starting or ending treatments

- Important occasions and milestones like birthdays, the first day of school, or holidays

Strength, hope, and grief

You may hear people say, “I don’t know how you do it all. I don’t think I could handle it.” At times you may wonder if, or how you’ll get through the experience. At other times, you “just do it”, because there is no other choice, or because you’ll do anything for your child. This back-and-forth feeling is natural. Sometimes you may feel you can’t handle anything well, and that’s okay too. Being “strong” does not mean that you never feel weak, or cry, or think about giving up. Every parent copes and deals with things in different ways. Every parent has different ways of choosing treatment options, and different attitudes about what “hope” means. It takes a lot of strength to share worries, thoughts, and feelings, and to ask for and accept help.

One of the ways that serious illness is unique for children is that even as they get sicker or lose some abilities, they may still learn and develop new skills. These achievements can cause very mixed feelings, like hope and heartache, joy and sadness.

Being hopeful does not mean that you are never doubtful, or worried. “Hope” means different things to different people, and can change over time. You may hope:

- For your child to recover, for a new treatment, or for a “miracle”

- That your child will experience important moments before they die

- That your child is comfortable, with as little pain or discomfort as possible

- For a peaceful death

- That your family will “be okay” and will support one another after your child dies

It’s okay to hope for any or all of these things, or for something else entirely. It’s okay to hope for one thing and believe another, or to hope for two different things at the same time. Your hopes may change from day to day, or minute to minute. Hope, like grief, is personal and changes over time.

Focus on the positive

One way that some people cope with grief is to try to focus on the positive.

“Just take one day at a time, don’t plan too far ahead. That’s all I can say, try to have a positive attitude even when everything feels like the world’s coming down on you, just try and make the most of it.” – Mother of a child with an advanced illness

This suggestion may work when things are calm or going well. But if you are grieving or struggling, it’s very hard to feel positive. Focus on the positive if it makes sense for you and your family.

Do "normal" activities

Another way to cope with grief is to create moments that feel “normal”. You may have to change some activities to create a “new normal”. For example:

- Watch your child’s hockey team even if your child can’t play

- Go to school, even if only for a short visit

- Have sleepovers in the hospital instead of at home

- Bring friends to the hospital for a movie night

- Host a “mini-prom” in the backyard

- Go for a wheelchair ride around your neighbourhood

- Use online meeting tools like Zoom or Facetime to facilitate group or one-on-one “play dates”, classroom attendance, or visits with family and friends

These ”normal” moments give you a break from the intense grief and they can help your family and friends enjoy happy times together.

“There is space inside us to hold all of these emotions, including grief and happiness at the same time.”